Tanto por su trayectoria fotográfica como por la mirada mágica y cotidiana con que plasma sus imágenes, Kati Horna es una de las personalidades más destacadas en el ámbito cultural mexicano. Nacida en Hungría, en 1912, radicó en la Ciudad de México por más de 60 años, desde fines de 1939 hasta su muerte en el 2000. (Fuente: http://elrincondemisdesvarios.blogspot.com/2012/04/kati-horna-fotografa-el-compromiso-de.html)

jueves, 29 de noviembre de 2012

Kati Horna - Fotográfa

Tanto por su trayectoria fotográfica como por la mirada mágica y cotidiana con que plasma sus imágenes, Kati Horna es una de las personalidades más destacadas en el ámbito cultural mexicano. Nacida en Hungría, en 1912, radicó en la Ciudad de México por más de 60 años, desde fines de 1939 hasta su muerte en el 2000. (Fuente: http://elrincondemisdesvarios.blogspot.com/2012/04/kati-horna-fotografa-el-compromiso-de.html)

Trotsky, Rivera, Bretón (México, 1938)

|

| Trotsky, Rivera, Bretón. México, 1938. |

Trotsky, Breton and Rivera reclaim the revolutionary potential of art.

Excerpts from André Breton in Mexico: Surrealist Visions of an “Independent Revolutionary” Landscape by Nathaniel Hooper Zingg, BA:

In his first 1924 manifesto, Breton defines “surrealism” as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express [...] the actual functioning of thought” (26). The “automatic writer” is a mere “recording vessel” logging whatever might emerge (by chance) from an unimpeded flow of (unconscious) images (27-8). But even in the first manifesto, not everything that results from this mere “recording” exercise is equally potent: the most “surreal” moments are disruptive, jarring juxtapositions of two very different images. A surrealist “metaphor” is an uncanny clash, a logically irreconcilable combination of seemingly random ephemera.

Metaphor’s process of conjoining “distant realities” constitutes a type of “alchemy” for Breton (see Balakian 34). As Anna Balakian has noted, surrealist metaphor is not about finding “correspondences” between this “world” and a more perfect one of forms as in the philosophy of Emanuel Swedenborg and the symbolist writings of Charles Baudelaire (35). Rather, the coming-together of objects from “logically unrelated” spheres is more akin to a generative process of metamorphosis; these fragments of reality, in their surrealist juxtaposition, “become something else:” an alchemical reaction (Balakian 36).

miércoles, 28 de noviembre de 2012

Maruja Mallo (1902-1995, Española). Pintora.

Maruja Mallo was born in Viveiro (Lugo) in 1902. Her real name was Ana María Gómez González. In 1922 she moved to Madrid with her family. She studied at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where she met Salvador Dalí, who introduced her to the world of Surrealism and the Generation of '27. She illustrated poems by Rafael Alberti, such as "La pájara pinta". In 1927 she met Ortega y Gasset, and worked as an illustrator for "Revista de Occidente". Her first solo exhibition took place in the halls of said publication, and proved to be very successful. In the 1930s she travelled to Paris, where she met André Breton, amongst others, and her work became immersed in Surrealism. Back in Spain she worked as a teacher. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, she was exiled to Argentina. In 1939 she painted her most important work: "El canto de la espiga". She returned to Spain in the 1960s. She died in Madrid in 1995. (Source: http://www.spainisculture.com/en/artistas_creadores/maruja_mallo.html)

Ana María Gómez González, nombre real de Maruja Mallo, nació en Viveiro en 1902.

En la Residencia de Estudiantes tomó contacto con el Surrealismo y la Generación del 27, especialmente con Buñuel, García Lorca, Alberti, Dalí y Pepe Bello. Conocía a Dalí.

En 1927, conoce personalmente a Ortega y Gasset y comenzó a colaborar como ilustradora en la Revista de Occidente, donde realizó su primera exposición individual, que tuvo un gran éxito.

Cuatro años después de su primera exposición, una pensión de la Junta de Ampliación de Estudios de Madrid le permitió viajar a París, donde tomó contacto con el grupo surrealista francés. En este momento su pintura sufrió un cambio radical. Basándose en las consignas del Manifiesto de André Bretón, realizó una serie tremendista llamada Cloacas y Campanarios, donde los protagonistas eran tétricos esqueletos, espantapájaros y cloacas.

En los años previos a la Guerra Civil, tras su estancia en París, y sobre todo debido a su inclusión en el grupo de Torres García, realizó composiciones basadas en estudios geométricos, intentando crear un lenguaje universal basado en los principios de la geometría.

Tras el estallido de la Guerra Civil, se exilió a Buenos Aires, donde siguió con su trabajo pictórico y realizando numerosas exposiciones, colectivas e individuales, además de impartir conferencias, tanto en Argentina como en Chile o Uruguay, países que visitaba con frecuencia. Se integró en el contexto americano relacionándose no sólo con los intelectuales exiliados, sino también con los de los países que visitaba, sobre todo a través de Pablo Neruda y Victoria Ocampo.

En 1961 volvió definitivamente a España, instalándose en Madrid, donde retomó la colaboración con la Revista de Occidente. En esta época, la temática de su pintura está condicionada por el interés de la pintora por las ciencias ocultas y el esoterismo.

Falleció en Madrid en febrero de 1995, pocos después de que el Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea realizase su primera exposición antológica en España.

(Fuente: http://es.globedia.com/ciclo-conferencias-maruja-mallo-real-academia)

martes, 27 de noviembre de 2012

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Raices, 1943.

|

| Raíces, 1943 |

- Carta enviada a Diego Rivera por Frida Kahlo

el 8 de Diciembre de 1938, cuando el cumplia 52 años -

Niño mio de la gran Ocultadora, son las seis de la mañana y los guajolotes cantan. Calor de humana ternura. Soledad acompañada. Jamás, en toda la vida, olvidaré tu presencia. Me acogiste destrozada y me devolviste entera, íntegra.

En esta pequeña tierra ¡ dónde pondré la mirada? ¡ Tan inmensa, tan profunda! Ya no hay tiempo , ya no hay nada. Distancia. Hay ya soló realidad. Lo que fue, ¡ fue para siempre! Lo que es, son las raíces que se asoman transparentes, transformadas en árbol frutal eterno. Tus frutos ya dan sus aromas, tus flores dan su color creciendo con la alegría de los vientos y la flor.

Nombre de Diego, nombre de amor. No dejes que le dé sed al árbol que tanto te ama, que atesoró tu semilla, que cristalizó tu vida a las seis de la mañana.

No djes que le dé sed al árbol del que eres sol, que atesoró tu semilla. es Diego nombre de amor

TU FRIDA

Alice Rahon (1904-1987. French, Mexican). Hindone Night, 1953.

lunes, 26 de noviembre de 2012

Leonora Carrington. Sidhe: The white people of Tuath Dé Dannan, 1954.

--Leonora Carrington

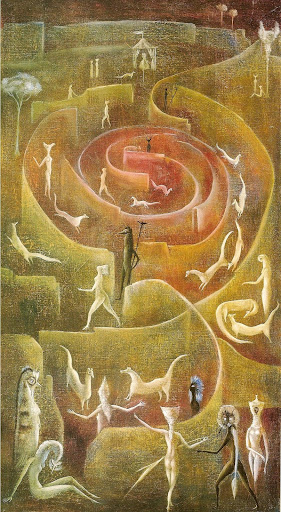

Leonora Carrington (1917-2011. English, Mexican.). Ferret Race, 1950-51.

“Aunque me atraían las ideas de los surrealistas, no me

gusta que hoy me encajonen como surrealista.

Prefiero ser feminista. André Breton y los hombres del grupo eran muy

machistas, sólo nos querían a nosotras como musas alocadas y sensuales

para divertirlos, para atenderlos. Además mi reloj no se detuvo en ese

momento, sólo viví tres años con Ernst y no me gusta que me constriñan

como si fuera una tonta. No he vivido bajo el embrujo de Ernst: nací con

mi vocación y mis obras son sólo mías.”

“Aunque me atraían las ideas de los surrealistas, no me

gusta que hoy me encajonen como surrealista.

Prefiero ser feminista. André Breton y los hombres del grupo eran muy

machistas, sólo nos querían a nosotras como musas alocadas y sensuales

para divertirlos, para atenderlos. Además mi reloj no se detuvo en ese

momento, sólo viví tres años con Ernst y no me gusta que me constriñan

como si fuera una tonta. No he vivido bajo el embrujo de Ernst: nací con

mi vocación y mis obras son sólo mías.”--Leonora Carrington

Remedios Vario (1908-1963. Española, Mexicana). Premonición, 1953.

Según la Revista Clarín (25 de septiembre 2008): Remedios Varo se hizo mexicana por elección. Como Constancia de la Mora, Concha Méndez o Carlota O’Neill, sucumbió al hechizo del Popocatepetl. Hay viajes que ya no tienen retorno y en México Varo se hizo más surrealista que nunca, tal vez porque no contaba con la presencia directa de sus mentores franceses. Por fin encontró el tiempo oportuno para crear. Las guerras quedaban atrás, al igual que las fugas provisionales. En México encontró una vertiente más inquietante del surrealismo, alentada por espíritus tan refinados y tortuosos como Frida Khalo y Leonora Carrington. Con esta última, a la que consideraba «hermana gemela del alma» Varo exploró nuevos caminos pictóricos y espirituales, fueran estéticas arriesgadas o filosofías herméticas u orientales.

Diego Rivera. Vendedora de Flores, 1949.

| Diego Rivera. Vendora de flores, 1949. |

| "¿Las mujeres que he amado? Tuve la suerte de amar a la mujer más maravillosa que he conocido. Ella fue la poesía misma y el genio mismo. Desgraciadamente no supe amarla a ella sola, pues he sido siempre incapaz de amar a una sola mujer. Dicen mis amigos que mi corazón es un multifamiliar. Por mi parte, creo que el mandato “amaos los unos a los otros” no indica limitación numérica de ninguna especie sino que antes bien, abarca a la humanidad entera." --Diego Rivera (La Jornada. Entrevistado por Elena Poniatoska.) |

domingo, 25 de noviembre de 2012

sábado, 24 de noviembre de 2012

Nymphaea odorata y la semana de las letras

El placentero quehacer de la traducción de los poetas del Sur de la Semana de las letras y la lectura de Rosario, Argentina, me lleva por los inesperados vericuetos de la historia del nenúfar, su arquitectura carnosa, ilustración, usos medicinales y olor, por las geografías y las formas del pez mojarra, originario de África, por la etimología guaraní que desemboca en el cauce actual e historico del río Paraná y por las ilustraciones botánicas italianas de claveles dibujadas con mano fina. Entro en los bosques de internet para estudiar sus sujetos, como si entrara en la vastedad de las Amazonas, para adentrarme en sus palabras, orígenes y contextos, redescubriendo continentes y tiempos que cada uno lleva en su corazón.

Y luego, vuelvo otra vez a Tamayo, porque sí, porque México, y porque si tienes que preguntar por qué, no entiendes el juego infantil, ni la rosa mexicana, ni de pulque, ni de pilas de lavar, ni de calles de tierra que hay que barrer, ni cómo moler el nixtamal sobre el metate, esencias que se graban para siempre una vez vividas. Si tienes que preguntar por qué o no entiendes o más bien te has olvidado lo que una vez entendiste, para comprender no hace falta ser mexicano. No hace falta más que salir bajo el signo del alma y sentir sus estrellas intemporales.

***

-- Lorena Wolfman © 2012

Y luego, vuelvo otra vez a Tamayo, porque sí, porque México, y porque si tienes que preguntar por qué, no entiendes el juego infantil, ni la rosa mexicana, ni de pulque, ni de pilas de lavar, ni de calles de tierra que hay que barrer, ni cómo moler el nixtamal sobre el metate, esencias que se graban para siempre una vez vividas. Si tienes que preguntar por qué o no entiendes o más bien te has olvidado lo que una vez entendiste, para comprender no hace falta ser mexicano. No hace falta más que salir bajo el signo del alma y sentir sus estrellas intemporales.

***

The pleasant task of translating poets of the Southern hemisphere from the Week of Letters and Readings in Rosario, Argentina, takes me down unexpected paths like that of the history of the lotus, its fleshy architecture, illustration, medicinal uses and odor, or through the geographies and forms of the Mojarra fish, of African origin, through the guaraní etymology that flows into the current and historical riverbeds of the Paraná river, and through the italian botanical ilustrations of carnations drawn with a fine hand. I enter the forests of the internet to study their subjects, as though I were entering the vastness of the Amazon, in order to penetrate their words, origins and contexts, rediscovering continents and temportalities each one keeps in their hearts.

And then, I return again to Tamayo, just because, because Mexico, and because if you have to ask why, you don't understand children's games, nor Mexican rose, nor pulque, nor wash basins for washing by hand, nor the dirt streets that must be swept, nor how to grind the nixtamal corn on the metate, essences that are etched forever once lived. If you have to ask why, you don't understand or more likely, you have forgotten what you once knew-- in order to comprehend you don't have to be Mexican, it takes nothing more than to walk out under the sign of the soul and feel its intemporal stars.

And then, I return again to Tamayo, just because, because Mexico, and because if you have to ask why, you don't understand children's games, nor Mexican rose, nor pulque, nor wash basins for washing by hand, nor the dirt streets that must be swept, nor how to grind the nixtamal corn on the metate, essences that are etched forever once lived. If you have to ask why, you don't understand or more likely, you have forgotten what you once knew-- in order to comprehend you don't have to be Mexican, it takes nothing more than to walk out under the sign of the soul and feel its intemporal stars.

-- Lorena Wolfman © 2012

viernes, 23 de noviembre de 2012

Rufino Tamayo: Sandías, 1973

"Procuro ir más y más hacia lo esencial y decir lo que quiero con menos y menos elementos. Elimino detalles, por ejemplo los ojos cuando me sobran."

I attempt to go more and more towards what is essential and say what I want to with less and less elements. I eliminate details, the eyes, for example, when I don't need them.

***

"En cierta forma toda mi obra habla del amor. Yo contemplo la tierra y el espacio; observo, pinto y siento que va surgiendo en mi un gran amor."

In a certain way, my whole work speaks of love. I contemplate the earth and space; I observe, paint and I feel a great love welling up in me.

In a certain way, my whole work speaks of love. I contemplate the earth and space; I observe, paint and I feel a great love welling up in me.

***

"Soy mexicano, mi color es mexicano, mis figuras son mexicanas, pero mi

concepto es una mezcla. Soy un hombre igual a los demás hombres, con las

mismas aspiraciones y preocupaciones, dividido por los prejuicios y

nacionalismos, pero unido por la misma cultura, la cultura humana.

Soy mexicano, me nutro de la tradición de mi tierra, para dar al mundo y recibir del mundo cuanto pueda. Este es mi credo mexicano internacional."

I am Mexican, my color is Mexican, mi figures are Mexican, but my concepts are a mixture. I am a man like any other man, with the same aspirations and worries, divided by prejudice and nationalism, but united by the same culture, the human culture.

I am Mexican, I am nourished by the traditions of my country, to order to give to the world and receive from the world as much as I can. This is my international Mexican credo.

--Rufino Tamayo

jueves, 22 de noviembre de 2012

Río Paraná. La Cuenca de la Plata.

El nombre del río procede de las palabras guaraníes para, "mar", y na, "semejante", "parecido", que expresan el gran volumen de su caudal.

Its name comes from the Guaraní words para, "sea", and na, "like" or "similar", which express the great volume of its flow.

***

El río Paraná en su tramo argentino se encuentra en estado “casi natural”. La poca intervención humana da oportunidad a los investigadores de conocer su comportamiento y explorarlo como si fuera un gran laboratorio natural. Es uno de los ríos más estudiados del mundo.

The Paraná river, in its Argentine leg, is in an "almost natural" state. The relatively light human invention gives investigators the opportunity to get to know its behavior and explore it as though it were a great natural laboratory. It is one of the most studied rivers in the world.

***

El Paraná se transforma y el río que vemos hoy no es el mismo que hace 40 o 100 años. Esos cambios van de la mano de las fluctuaciones en el clima de la región.

The Paraná changes over time, the river we se today is not the same one we saw 40 or 100 years ago. These changes go hand in hand with climactic changes in the region.

***

Los conquistadores españoles utilizaron el río Paraná como vía de penetración hacia el interior del continente sudamericano en su búsqueda de la mítica sierra de la Plata.

The Spanish conquistadors used the Paraná as a route to penetrate into the interior of the South American continent in their search for the mythic mountain range of la Plata.

Water lilt. Nymphoeaceoe. Nelumbium luteum. Wankapin. Sacred bean. Indian Lotus. Nymphea Nelumbo. Water nymph.

This section is adapted from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana.

Water Lilt

Water Lilt, a name for aquatic plants of several distinct genera included under one family, the nymphoeaceoe, or water lily family, which is far removed from the lily family proper, as that consists of endogenous plants, while these are exogens.

Members of the family have submerged rootstocks, from which, in those popularly known as water lilies, arise long-petioled leaves and scapes bearing large, solitary, and generally showy flowers; both leaves and flowers usually float, but are sometimes emersed (i. e., project above the water); the fruit in some matures above, and in others beneath the water.

The most common native water lily in North America is the yellow, nuphar advena, also called yellow pond lily and spatterdock; this is found far north in Canada, extending to Sitka, and southward to Florida and Texas, in still or stagnant water.

For the genus nuphar (from Gr. vovjxip, the ancient name) the leaves are floating or emersed and erect, with stout petioles; the flowers, produced all summer, are on fleshy stalks, and not showy, being of a dull yellow color, sometimes tinged with purple or greenish on the outside; the calyx, of five or six sepals, is very large, and is usually taken for the corolla; but the true petals are numerous small thick bodies, which appear much like the manyshort stamens next to which they are placed; the large columnar ovary is truncate, at the top, crowned by the disk-like, many-rayed stigma, and has 10 to 25 cells, with numerous ovules in each cell; it usually ripens above water, becoming fleshy.

The common species, AT. advena, has six sepals, while the less common AT. lutea has five, with its early leaves submersed and very thin, the floating ones oval; this is common in Europe, where its different forms have been named as species, and a small variety of it (var. pumila) is more common in this country than the type. A southern species, N. mgittavfolia, has arrowshaped leaves a foot long and only 2 in. wide.

Sweet-scented Water Lily (Nymphaea odorata).

The plant known especially in the United States as the water lily, frequently as pond lily, and sometimes as water nymph, belongs to the genus nymphcea, it having been dedicated by the Greeks to the water nymphs. In this the sepals are four, green on the outside, but petal-like within; the petals are very numerous, in several rows, the inner ones becoming narrower and smaller until they gradually pass into stamens, which are also numerous and, with the petals, attached to the surface of the many-celled ovary, which bears at the top a globular projection with radiate stigmas, each of which bears an incurved sterile appendage; the fruit, which ripens under water, is berrylike, pulpy within, and each of its numerous seeds is enveloped in a thin membranous sac.

Our common species, N. odorata, has nearly orbicular leaves, which often cover a broad surface of water on the margins of lakes and ponds, forming what are known as lily pads; the flowers, which open very early in the morning, are often over 5 in. across, of the purest white, and most delightfully sweet-scented. The flowers vary considerably in size, one (var. minor) being only half as large as the ordinary form; in some localities the flowers are slightly tinged with pink, and they are found, though rarely, with the petals bright pink throughout; the leaves also vary in size, and sometimes are crimson on the under side.

The rootstock, as large as one's arm or larger, and several feet long, is blackish externally, and marked with scars left by the leaves and flower stems; it is whitish and spongy within, and has an astringent and bitterish taste; it is in repute among botanic physicians as a tonic and astringent. Though the plant often grows in water several feet deep, the leaf and flower stalks accommodate themselves to the depth, and they may sometimes be found where there is but a few inches of water; the plants may be cultivated in a tub or shallow tank containing earth and kept well supplied with water.

Another species, so like the preceding in general appearance as to have escaped notice, was first distinctly identified and described in 1865 by Dr. J. A. Paine in his catalogue of the plants of Oneida co., N. Y. It differs from the other chiefly in its larger leaves, a foot or more wide; its larger flowers, 4½ to 9 in. across, which have broader and blunter petals and are nearly scentless, or at most with a slight applelike odor quite unlike the rich perfume of the preceding; and more especially in bearing numerous simple or compound tubers upon the rootstock, which resemble Jerusalem artichokes and spontaneously detach themselves from it, and on account of which Dr. Paine called it AT. tuberosa. It is found in central New York, southward and westward. - The common water lily of Europe and Asia is AT. alba, which closely resembles our AT. odorata, but its flowers have broader petals and are scentless.

There are several exotic species of great beauty, the best known is N. lotus, white, a native of Egypt, whose ancient inhabitants used the seeds as food; it is the white lotus of the Nile. AT. dentata, from Sierra Leone, has leaves sometimes 2 ft. across, and white flowers with a diameter of 14 in. The blue lotus of the Nile, AT. coerulea, has sweet-scented flowers, about the size of our own fragrant species, but of a charming blue color. Another blue species is N. gigantea from Australia, with flowers more than a foot across. There are other blue-flowered species, or varieties, as some regard them, and some with red flowers, such as N. rubra, from the East Indies. - The largest of our water lilies is one of the two species of nelumbium, so called from nelwmbo, the Ceylonese name of the Asiatic species.

Ours, N. luteum, called sacred bean, water chinquapin, and sometimes nelumbo, is found in the western and southern waters, and in a few isolated localities in Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and western New York, to which it is supposed to,have been introduced by the aborigines; the rootstocks are tuberous; the leaves stand high out of water; the blade, attached to the stalk by the centre and strongly ribbed, is often 2 ft. across, with a deep cup-like depression in the centre; the flowers, also emersed, are 5 to 6 in. across, the numerous sepals and petals alike, the many stamens slender, and the 12 to 40 ovaries imbedded in a disk or torus, which becomes 4 to 6 in. across, into the cavities in which the acorn-like nuts are set like plums in a pudding. This was an important plant to the aborigines, as the tubers, resembling in appearance those of the sweet potato, with a proper amount of boiling become quite farina-ceous, and, according to Nuttall, are as agreeable and wholesome as the potato; the seeds are also edible.

The other species, N. speciosum, is regarded as the sacred lotus of the ancient Egyptians; it grows throughout the East, but is no longer found in the Nile, though many sculptured representations of it remain; it is nearly like N. luteum, but has pink or rose-colored flowers and smaller stamens; the tubers and seeds are used as food in China and elsewhere, and the fibres of the leaf stalks as lamp wicks.

The grandest of all water lilies, from the tributaries of the Amazon, bears the name Victoria regia. Though it was discovered as early as 1801, and mentioned by subsequent travellers, it was not named till 1838, when Lindley described it and dedicated it to his sovereign; but it was not till about 1850 that it was introduced into cultivation through the efforts of the traveller Spruce.

In cultivation the Victoria is an annual, with a fleshy rootstock, from which are produced leaves from 6 to 12 ft. in diameter; these are fixed to the petiole by the centre," and have the margin turned up as a border 2 or 3 in. high, giving the leaf the appearance of a huge tray; their upper surface is of a rich green color, and studded with small prominences; the lower surface, purple or violet, is traversed by ridge-like veins, radiating from the centre, and connected by cross veins, which divide the whole into compartments; the veins and the leaf stalks are covered with spines or prickles.

These enormous leaves, especially adapted by their structure to float, are capable of sustaining the weight of a large water fowl, and by placing a board upon them to distribute the weight, they will hold up a child 10 years old. The flower is of two days' duration. The first day it opens about 6 o'clock P. M., and remains open until about the same hour the next morning; in this stage it is cup-shaped, 12 to 16 in. across, with numerous pure white petals, and emits a delightful fragrance. The second evening the flower opens again, but it presents an entirely different appearance; the petals are now of a rosy pink color, and reflexed, or bent downward from the centre, to form a handsome coronet, but now without odor; the flower closes toward morning, and during the day it sinks beneath the surface to ripen the seeds. In South America the seeds are called water maize; they are very farinaceous, and are roasted and eaten.

Read more: http://chestofbooks.com/reference/American-Cyclopaedia-12/Water-Lilt.html#.ULEI04VFjyu#ixzz2DADJaiS8

domingo, 18 de noviembre de 2012

winter

we will walk

amidst the blades

of cold

our desire

will refuse to settle

amidst the fallen leaves

the wind will sound

its uneven music

admidst the naked branches

we will carry with us

the unsheathed swords

of memory

absorbing the heat

of a far off sun

will require patience

but it will still burn

--Lorena © 2012

amidst the blades

of cold

our desire

will refuse to settle

amidst the fallen leaves

the wind will sound

its uneven music

admidst the naked branches

we will carry with us

the unsheathed swords

of memory

absorbing the heat

of a far off sun

will require patience

but it will still burn

--Lorena © 2012

invierno

caminaremos

entre las navajas

del frío

nuestro deseo

se negará a acomodar

entre las hojas caídas

el viento sonará

su música dispareja

entre las ramas desnudas

llevaremos puestas

las desenvainadas espadas

del recuerdo

absorber el calor

de un sol lejano

requerirá paciencia

pero aún arderá

--Lorena © 2012

entre las navajas

del frío

nuestro deseo

se negará a acomodar

entre las hojas caídas

el viento sonará

su música dispareja

entre las ramas desnudas

llevaremos puestas

las desenvainadas espadas

del recuerdo

absorber el calor

de un sol lejano

requerirá paciencia

pero aún arderá

--Lorena © 2012

sábado, 17 de noviembre de 2012

domingo, 11 de noviembre de 2012

packing my bags

today I'm packing my bags for a new life

they are almost empty

I don’t need titles nor adjectives nor adverbs

at most an apple

a serpent follows me

belly to the earth

the pulse of my steps

abandons my feminine heritage

the marrow of the road

blooms before me

perhaps I have already died

from a past that was not even mine

who was she who died

of whom were her desires of gender

of whom were her fears

well today asking no one’s permission

I prepare for a new life

-- Lorena Wolfman © 2012

they are almost empty

I don’t need titles nor adjectives nor adverbs

at most an apple

a serpent follows me

belly to the earth

the pulse of my steps

abandons my feminine heritage

the marrow of the road

blooms before me

perhaps I have already died

from a past that was not even mine

who was she who died

of whom were her desires of gender

of whom were her fears

well today asking no one’s permission

I prepare for a new life

-- Lorena Wolfman © 2012

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)